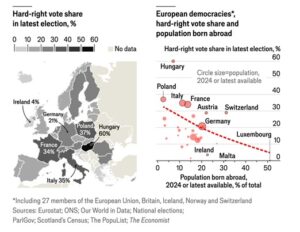

One of the biggest stories surrounding the result of the recent German election has been the performance of the far-right AfD, now the second-largest party in Germany’s legislature, the Bundestag. This is in line with the broader trend of far-right gains fueled by the cost of living crisis and high levels of illegal immigration to Europe. In the UK, the populist Reform UK won 14.3% of the popular vote. In France, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally won the largest share of the vote in both rounds of the election (33.2% and 37% respectively). In some EU countries such as the Netherlands, the far-right has joined governing coalitions, whereas in Italy the far-right under Giorgia Meloni forms the Government. This political rise has prompted historically established parties, particularly the centre-right, to revisit their historic strategy of non-cooperation with far-right parties. This article will cover some of the various arrangements adopted by these established parties in response to the far-right.

With memories of the atrocities of World War 2 vivid in the minds of many political leaders, starting in the 90s European parties in some nations adopted a strict policy of political non-cooperation with the far-right. This included the exclusion of the far-right from Government formation and collaboration over legislation. The rationale behind this move was the belief that participation in Government by far-right parties would lead to an erosion of democratic institutions and checks and balances. The belief at the heart of this strategy is that by excluding far-right parties from access to Government ministries and policy formulation, their often illiberal and extreme views cannot be implemented, hindering the party’s growth in the long term. By excluding such parties from mainstream politics, it would de-legitimize them and portray them as extremists. It would prevent the de-sensitization of bigotry and hateful ideology. It was believed that the normalisation of relations with the Nazis is what led to their eventual dominance in Germany. Such an arrangement came to be known as a Cordon Sanitaire. As a result of this arrangement, far-right parties have never participated in the Governments of most European countries. It is important to note that coordination have different levels. Passive support over legislation does not involve the same level of cooperation as government formulation. Where the Cordon Sanitaire is drawn within these various levels of cooperation with extremist parties varies from country to country.

Beyond ideological containment, there are various strategic reasons as to why such an arrangement may also come into place. Collaborating with “the establishment” may tarnish this outsider image among some supporters. As a result, such parties generally pitch themselves as “anti-establishment” and as a result, they adopt extreme policy positions which they refuse to compromise on, making it difficult to collaborate with them. As a result, populist parties that enter Governments often fail to live up to expectations formed during campaigning. In Finland, the Finn’s Party, which entered into Government with the centre-right National Coalition in 2023 has slumped in polling as a result of racism scandals and unpopular economic decisions such as austerity, despite campaigning as an economic populist party.

The Cordon Sanitaire is also useful for parties participating in this agreement on the opposite end of the political spectrum from the cordoned party since it limits their direct policy influence on the Government. Naturally, since extreme policies of one side are excluded from policy formulation, the party on the opposite side of the issue has more influence over Government decision-making. This is based on the assumption that excluding the party from coalitions, won’t pressure established parties from incorporating their policies. An example of the latter can be seen in Germany itself, where before the election, the centre-right CDU (which won the subsequent election in a landslide), passed a motion in the Bundestag to restrict migration. While not directly incorporating AfD policy, the CDU under Merz has shifted closer to the AfD on the issue. During the Brexit negotiations under PM Boris Johnson, the Conservative Party adopted a “Hard Brexit” stance similar to that of Nigel Farage’s populist United Kingdon Independence Party. This way, parties considered extreme were still able to impact Government decision-making. Therefore of all the perceived advantages of a Cordon Sanitaire, this is probably the weakest.

Another strategic objective of a Cordon Sanitaire is to limit support for extremist parties by promoting strategic voting. By excluding a certain party from coalitions, established parties may attempt to display a vote to the party as a waste. If voters feel that their views won’t be represented in Government, they may instead vote for a party that they think could implement policies closest to them. Such voting is a form of “strategic voting”. This is based on the assumption that voters vote on the basis of whether they think their policies will be actually represented in Government rather than simply whether a party represents their views or not. This encourages mainstream parties to adopt the policies of ostracized parties to attract their voters to vote for a party that “can actually govern”.

Focusing first on ideological constraint, the far-right has rapidly gained popularity in major European countries despite exclusion, and many of their ideas have entered the mainstream of European politics. The “Patriots of Europe” hard right political grouping finished 3rd in the 2024 EU parliamentary election, despite fragmentation of the hard to far right into 3 separate political factions (ECR, PfE and ESN). Support for anti-immigration policies has steadely increased over time, as have instances of hate crime and discrimination according to the EU Agency for Fundamental Human Rights. It is clear that right wing extremism has grown in Europe. At the same time, consistent protests against the far-right in Europe has demonstrated a sensitization to its perceived dangers. For example, after far-right riots erupted in the UK in July and August of 2024, opposition to the rioters mobilised in the form of counter protests led by anti-fascist and immigrant groups. After the passage of the German anti-immigration motion mentioned earlier, thousands of protestors mobilised across various cities in Germany against the AfD.

As for strategic objectives, the Cordon Sanitaire has significantly weakened across Europe due to logistical impossibilities resulting from the political ascent of the far-right. Far-right parties have continuously made the case that the cordon sanitaire is undemocratic, elitist and a way for the establishment to protect themself. Exclusion has bolstered their anti-elitist and anti-establishmentarian credentials. Over time, centre-right parties have shifted rightwards to account for the increase in right-wing sentiment in Europe. At the same time, extremist parties have signalled a willingness to cooperate in order to enter government. As a result, collaboration with the far-right has become less inconvenient for mainstream parties. Collaboration has also increased due to political standstills, particularly at local levels. The mainstream parties often do not have enough votes by themselves to form a Government, leading either to extremely unstable coalitions (The Netherlands between 2017-21) or minority governments (presently France and Sweden). The rightward shift of conservative parties has also allowed some traditionally hard-right policies, such as with the case of a hard Brexit in the UK, to enter government policy consideration via historically mainstream parties. Nevertheless, exclusion has so far prevented major far-right policy aims especially regarding immigration, asylum and citizenship from being enacted. Mainstream parties have maintained exclusion even when the political cost outweighs the benefits, turning the arrangement into a social norm enforcement mechanism rather than a mere political strategy.

Supporters of the Cordon Sanitaire state that it is necessary to keep the far-right out of Government and prohibit them from accessing state institutions since in most countries the far-right has still never entered Government. They also point to the necessity of keeping illiberal policies and perceived bigotry and racism out of Government. The image of the far-right in most European countries is still that of extremists. Supporters feel that the cordon sanitaire has succeeded in the most part from normalizing populist extremism. Critics argue that this arrangement is undemocratic, since it sidelines the views of a large portion of the electorate and “silence their voice”. Parties often ignore the genuine issues raised by such parties by refusing to cooperate with them. The Cordon Sanitaire also perpetuates the image of the far-right as anti-establishment and perpetuates the victim complex that these parties try to create. This has the effect of boosting their support since voters would always view such parties as an alternative to established politics. This arrangement also leads to political instability by creating unstable Governments. As a result, the cordon sanitaire has begun to fray, at least at local and state levels. In most countries, centrist parties have had to rely on far-right support to pass legislation at some or the other point. This is true for Germany at state and local levels and France and Spain at national levels, for instance.

The fraying of the cordon sanitaire and the creeping influence of far-right populism in European politics will have far-reaching consequences for the future of Europe in the world. With the election of Donald Trump, it is clear to European leaders that they cannot unconditionally rely on American security and diplomatic support and must establish an identity independent from that of the US. The far-right has historically struggled to define a coherent foreign policy position. Most right wing populist parties have a Eurosceptic history, blaming the EU’s right to free movement for Europe’s ineffectual response to the migrant crisis in 2015. The far-right’s eurosceptism is naturally compatible with Russian Foreign Policy, since Putin has long seen European integration as a threat to Russia. The Brexit movement was constituted in a large part of right wing populists and far-right groups. The movement was also marred with allegation of Russian involvement, as later confirmed by the “Brexit Report”, which also included broader allegations of Russian interference in British politics. The Party For Freedom in the Netherlands has historically advocated for “Nexit”, only moderating this position after entering Government and the AfD’s party platform includes withdrawal from the EU. The far-right also has a dubious record vis-a-vis support the Ukraine. This has led to accusations of being “Pro-Putin”, which has harmed the far-right movement since Europeans broadly continue to support continued aid for Ukraine.

Moving forward, the far-right’s lukewarm stance on Russia threatens European Unity, which appears stronger than ever in the light of the US scaling back support for Ukraine. Seeing broad popular support for Ukraine, many far-right parties have adjusted their stance towards the EU and Russia, such as in France and the Netherlands. Marine Le Pen’s National Rally has supported non-lethal aid to Ukraine and the PVV in the Netherlands has openly condemned the invasion of Ukraine. As far-right parties aim to break the Cordon Sanitaire against them and portray themselves as a serious political force capable of Governing, it must hammer a coherent policy on Russian expansionism (or lack thereof) as well as future structure of the European Union, which remains extremely popular amongst Europeans.