Introduction

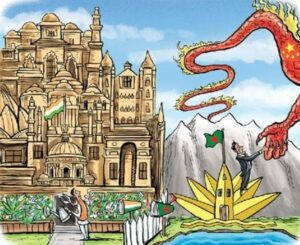

Otto von Bismarck, the Iron Chancellor of Germany, famously preferred diplomatic negotiations with Russia over England.[1]It was easier to please a singular Tsar than deal with constantly changing ministers beholden to perpetually unsatisfied parliaments. Novel practitioners of realpolitik (realist politics) often fall prey to this line of thought when they choose to engage with authoritarian strongmen. In the case of some countries, like Russia, it makes sense to engage with autocratic heads of State. However, other such regimes are often unstable. For example, in Myanmar both India and China chose to ignore Western calls for democratisation and the accompanying sanctions, instead engaging with the military dictatorship. The Generals now control only a fraction of the country.[2] Popular support is a necessary precursor to long term strategic stability in bilateral relations. Chinese investments as part of the Belt and Road Initiative have floundered in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Hungary and much of Africa because they refused to learn this valuable lesson.[3] Elite capture is a short term strategy that tends to antagonise local populations. Consequently, unpopular regimes make untenable promises. India should avoid making this mistake in Bangladesh, a country where New Delhi has long been trying to create a long-term strategically favourable environment.

Bangladesh’s Relevance to India

A pliant regime in Dhaka is necessary for India due to multiple reasons. Primarily, Bangladesh’s long and often porous border with disturbed/insurgency-prone regions in India’s northeast. The opening of a third front in the north east would be a strategic disaster for India. It has only recently managed to placate ethno-nationalist sentiments in the region. As unrest in Manipur has shown, even that project is long from complete and in an extremely precarious position. Therefore, it is imperative for New Delhi to ensure that whoever might be in power in Dhaka is cognizant of India’s national security needs. There is also the question of the multitude of Indians in Bangladesh, alongside a Hindu minority that forms almost a tenth of the population. The last time this minority was threatened it migrated to India en masse, causing a refugee crisis that forced Indira Gandhi to start the Bangladesh Liberation War.[4] A similar turn of events cannot be allowed to occur.

For this, Raisina Hill must lend unequivocal support to the current government, headed by a microfinance pioneering Nobel laureate, which seeks to restore independent democratic institutions and the separation of party and state.[5] Mr Yunus, the interim Prime Minister, faces the difficult task of delaying elections despite the dominant party demanding otherwise, fixing an economy that was just revealed to be massively farcical.

The Case for Ensuring Democracy in Dhaka

Why should India support democracy in Bangladesh? Because New Delhi needs the government in Dhaka to have a vested interest in anti-terrorism and anti-radicalism. This will be possible only under a liberal democratic political system. In a way, the student uprising has therefore presented a solution rather than a problem to Raisina Hill. Their demands for a liberal democratic order with respect for human rights and independent institutions are the exact recipe required for preventing radicalism, atrocities against minorities and other troublesome social phenomena in the long term. India should bet on the continued prominence of the youth and students, the largest chunk in a population experiencing plummeting birth rates.[6] It should shun dynastic politics and make it clear that it will not tolerate a military government. This would not only endear it to the current dominant faction in Bangladeshi politics but also ensure that the future institutional setup in the country is protective of both, its Indian and Hindu minorities. Another significant advantage this would have is to disempower radical elements within Bangladeshi society. By making liberal democratic politics the popular arena for social decisions, radical groups that rely on terror, violence and indoctrination will be naturally pushed to the fringes of power. Furthermore, this would also allow India to further align its foreign policy with that of America. By supporting democracy in Bangladesh firmly enough to ensure that it occurs, India can win liberal hearts in America, a good idea given what a toss-up the upcoming presidential election is turning out to be.

Strategic and Military Necessities

There is also a strategic angle here. India cannot dare to threaten uncooperative governments in Dhaka for fear of pushing Bangladesh into Beijing’s waiting arms. A more dependable approach would be to lobby for a higher level of military interlinking, based on shared values of democracy and human rights. After all, the nation which poses the greatest military risk to Dhaka is India. Instead of competing with China for arms procurement, India should seek to align Bangladeshi defence policy with itself in a way that makes the entire competition moot. The aim should be to create a level of military integration between the armies and navies so that Bangladesh would prefer to rely on Indian defences rather than attempt to create its own through Chinese alternatives. You know what’s cheaper than a Chinese battleship? Needing no battleship at all.

This approach towards military interlinking would have larger strategic advantages as well. The fundamental problem in Indian military doctrine is that China and Pakistan use their borders with India to keep strategic focus on its land armies, thus forcing it to forgo the immense strategic advantages that would accompany a strengthening of the Indian navy.[7] By integrating Bangladesh into its defence orbit, India achieves a twofold victory. First, it removes a major strategic burden on its navy by befriending a potential rival that owns significant assets in the Bay of Bengal. Second, it creates a deeper incentive for American funding and naval technologies to be transferred to India to supplement its deterrence of China. Nuclear submarine technology shared with Australia under AUKUS (a trilateral security pact signed by Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) was not given to India due to American hesitance.[8] By increasing its strategic influence, as well as reinforcing its commitment to democracy internally as well as abroad, India can ease American fears that it will become the second China. Rather than ‘hiding and biding’ its time, India should openly proclaim its goals of a non-aggressive foreign policy and greater trade links.

International Welfarism

Instead of leaders, India should focus on winning the hearts of the Bangladeshi people. A poor country with a governmental apparatus dependent on NGOs offers an easy pathway for direct outreach. A close ally, Japan, is the largest source of aid to Bangladesh.[9] Indo-Japanese collaboration would conveniently allow both countries to prevent China from gaining another pearl (ally) in the neighbourhood. Moreover, over two-thirds of land in Bangladesh is liable to flooding, a figure that is bound to worsen with global warming.[10] Indian largesse in disaster relief efforts would endear the country directly to millions in Bangladesh while requiring relatively little investment. Build someone a bridge and they like you till someone comes along and builds them a better one, save their family from drowning and they will owe you gratitude for life.

The reverse can also apply. Earlier, India and Bangladesh suffered many of the same issues regarding low female workforce participation, illiteracy and lax healthcare. However, Dhaka has seen much greater success in improving the quality of life without the economic growth that many in New Delhi see as a prerequisite for human development.[11] Welfare-obsessed politicians should embrace this opportunity to learn. India could also use experience regarding organic indigenous NGO creation and operation given recent controversies regarding foreign subversion in the sector.

Economic Reintegration

Furthermore, while the Chinese economy has developed in a consumption-averse manner that inherently leaves less room for Bangladeshi goods, the Indian economy in this stage can readily integrate itself with the country. The local economies were severed during partition to a large extent, with raw material processing dominating the territories of Bangladesh while the Indian side held on to processing and manufacturing capabilities.[12] Instead of letting old wounds fester, reintegration would benefit both economies. Trade within the Indian Subcontinent is pitifully low, and there is much room for growth.[13] As Bangladesh grows closer to losing the preferential trading agreements accompanying its status as an underdeveloped country, it will naturally seek economic allies. Perhaps the best way to safeguard both Indians and Hindus in Bangladesh might be to make the country economically dependent on India.

Conclusion

As a country that has reduced its population growth at an extremely fast pace, Bangladesh’s demographic dividend will pay off in a short but glorious era. India should position itself to reap its benefits economically while avoiding its consequences militarily. Ultimately, ensuring that Bangladesh ends up a country of middle-class pensioners in fifty years is much better than watching it devolve into a poor, overpopulated wasteland with endless radicalised hordes utilising every opportunity to spread havoc in the mountainous borderlands. India already has one of those in the West

[1]Alan John PercivaleTaylor, “Bismarck: The Man and the Statesman”, H. Hamilton, 1955.

[2] Zo Tum Hmung; John Indergaard, “Time is Running Out for India’s Balancing Act on the Myanmar Border”, United States Institute of Peace, 15 Jun 2023.

https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/06/time-running-out-indias-balancing-act-myanmar-border

[3] Tessa Wong, “Belt and Road Initiative: Is China’s trillion-dollar gamble worth it?”, BBC, 17 Oct 2023.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-67120726

[4] Anam Zakaria, “Remembering the war of 1971 in East Pakistan”, Al Jazeera, 16 Dec 2019.

https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2019/12/16/remembering-the-war-of-1971-in-east-pakistan

[5] Ruma Paul, “Bangladesh Nobel laureate Yunus named chief adviser of interim government”, Reuters, 7 Aug 2024.

[6] “Bangladesh has ousted an autocrat. Now for the hard part”, The Economist, 8 Aug 2024.

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2024/08/08/bangladesh-has-ousted-an-autocrat-now-for-the-hard-part

[7] Aijaz Hussain, “India begins to flex its naval power as competition with China grows”, Associated Press, 2 Feb 2024.

https://apnews.com/article/india-china-maritime-security-d53925a976e667f275024fa964818c8f

[8] Dinakar Peri, “AUKUS focus is on submarine tech., there is no room for a fourth nation: sources” The Hindu, 27 Mar 2023.

[9] “Economic Relations with Japan”, Embassy of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh in Tokyo, Jan 2024.

[10] “Bangladesh (LEDC)”, Coolgeography.co.uk

[11] Atif Choudhury, “How Bangladesh’s NGO-Driven Development Model Compares to Authoritarian Alternatives”, Oxford Political Reveiw, 26 Aug 2024.

[12] Adnan Mazedul and Islam Khan, “Textile Industries in Bangladesh and Challenges of Growth”, Research Journal of Engineering science(2. 33-42) 2013.

[13] Colombo and Matarbari Port, “The Bay of Bengal should be an economic superpower”, The Economist, 18 Jul 2024.

https://www.economist.com/asia/2024/07/18/the-bay-of-bengal-should-be-an-economic-superpower